History

The Estonian National Museum is considered a memory institution that has emerged as part of the national movement, having served the cause ever since, though ambivalently during the Soviet regime. The museum was established in 1909 as a national museum with the aim of becoming an institution dedicated to preserving Estonian culture. The museum was tasked with collecting, preserving, researching and introducing ethnographic and cultural-historical material and folklore. The ENM became an important research base for Tartu University and the museum’s researchers started teaching ethnology at the university. During the period between the two world wars, the ENM developed into a central institution of cultural research in Estonia.

The initial idea to establish a museum as a representation of ethnic Estonian culture was formulated in the 1860s during the Estonian national awakening movement by the intellectuals of Estonian origin. The eventual museum mainly grew out of the collecting initiatives of two scholarly societies in Tartu: the Gelehrte Estnische Gesellschaft (Learned Estonian Society, founded in 1838) and the Eesti Üliõpilaste Selts (Estonian Students’ Society, founded in 1870) which collected artefacts of Estonian origin alongside with poetic and narrative forms of folklore. These active intellectuals of the period were greatly inspired by similar activities in Finland.

A direct incentive for the foundation of the museum came in 1907 with the death of Pastor Dr. Jakob Hurt who's extremely large and prominent folklore collection needed a permanent repository. The original statute of the museum (1908) envisioned it to be a grandiose institution that would house documentations of folklore, language, material artefacts, folk music and art collections, a library etc., with a focus on Estonian peasant culture that appeared to be rapidly changing under the pressures of modernisation and urbanisation at the turn of the century.

The main focus of the museum was put on collecting ethnographic objects and repertoires, which was carried out with the assistance of volunteers: schoolteachers, pastors, artists, writers, and students. In the first seven years about 170 volunteers collected around 20,000 objects from all over the country. The ENM did not have its own building and held first temporary exhibitions elsewhere, such as at theatres or in private apartments.

From 1920s

The situation improved radically with the establishment of the independent Republic of Estonia. In the 1920’s ENM went under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education. The state assisted the museum to obtain the property of the Raadi Manor, which offered a large space for exhibiting Estonian folk culture and where the permanent exhibition was opened in 1927. The museum director, young scholar from Finland Ilmari Manninen was recponcible for exhibition curating, in 27 exhibition halls, including folk culture, archeology, art and Finno-Ugric peoples exhibitions.

From 1940s

By 1940, the museum had became a significant centre of national and folk culture, with its four autonomous subdivisions collections of material and spiritual culture Estonian Folklore Archives, Archive Library, establishment of Estonian Bibliographical and Estonian Cultural History Archives.

Following the incorporation of Estonia into the USSR, the ENM was nationalised and divided into two distinct institutions: ENSV Riiklik Etnograafiamuuseum (the State Ethnographic Museum of the Estonian SSR) that had to deal more narrowly with the preservation and research of material culture, and Riiklik Kirjandusmuuseum (the State Literary Museum), to house the sub-units focused on collecting folklore, written documents and books. The Raadi Manor was destroyed during the war, though the collections that had been evacuated from the military zone remained largely intact. The war and the following Stalinist period of persecution and oppression meant the loss of the building, as well as severe impairment of the museum personnel.

By the end of the 1950s, the functioning of the ENM was restored within the framework of the Soviet closed political-scientific system. Under the conditions of “frozen” national ideology and identity, Estonian ethnology (ethnography) continued its pre-war direction, focusing on the research of “traditional” culture. The topics Estonian ethnographers focused on were: farm architecture, agricultural tools, and folk art costumes of the past peasant society. The dominant historical perspective through which material objects were seen remained the relatively safe evolutionistic descriptive approach, which allowed the avoidance of ideological manipulation, inevitably related to social contextualization of the present.

In terms of institutional structure, the museum at first came under the jurisdiction of the Estonian SSR Academy of Sciences (1946-1963) which facilitated scientific research. In the 1960s, more emphasis was placed on the research of Finno-Ugric cultures. The diversity of its collections, and the scientific research performed in this field allowed ENM became one of the central research institutions in the Soviet Union. During the Soviet period, the Ethnographic Museum was not able to exhibit a comprehensive display of Estonian folk culture due to lack of an exhibiting space, the permanent display had closed in the 1970s.Thus the museum transformed into a sort of an archive, with the public having limited access – rare visitors were proudly shown the neatly organized depositories.

From 1990s

In the 1990s the ENM had to once again focus on the general public, in order to make society aware of its mission, to justify its existence and endurance. After regaining independence in 1991, in the ‘period of national awakening’ when the country underwent major reforms, this became the most important task of the museum, alongside with aspirations to build new facilities for the museum. In 1994 a permanent exhibition “Estonia: Land, People, Culture” was opened.

A continuous idea to build a new ENM also means that conceptualisation of the museum and its social purpose was undergoing change. On the one hand, there has been the necessity to define identities at a time of rapid change by locating and securing old values and repaying history’s debts. The reinvention of the museum at the 1990s was closely connected to the questions of collective memory and collective identity, which have in turn also been affected by a return to the European fold. On the other hand, the ENM became part of the negotiations of the wider historical framework of negotiating the European and Estonian recent post-war history.

Since 2004, the ENM is the organizer of the annual documentary film festival World Film Festival/Maailmafilm, dedicated systematically to presenting visual anthropology and anthropological documentaries with rigorous analytic approach to world cultures.

From 2016

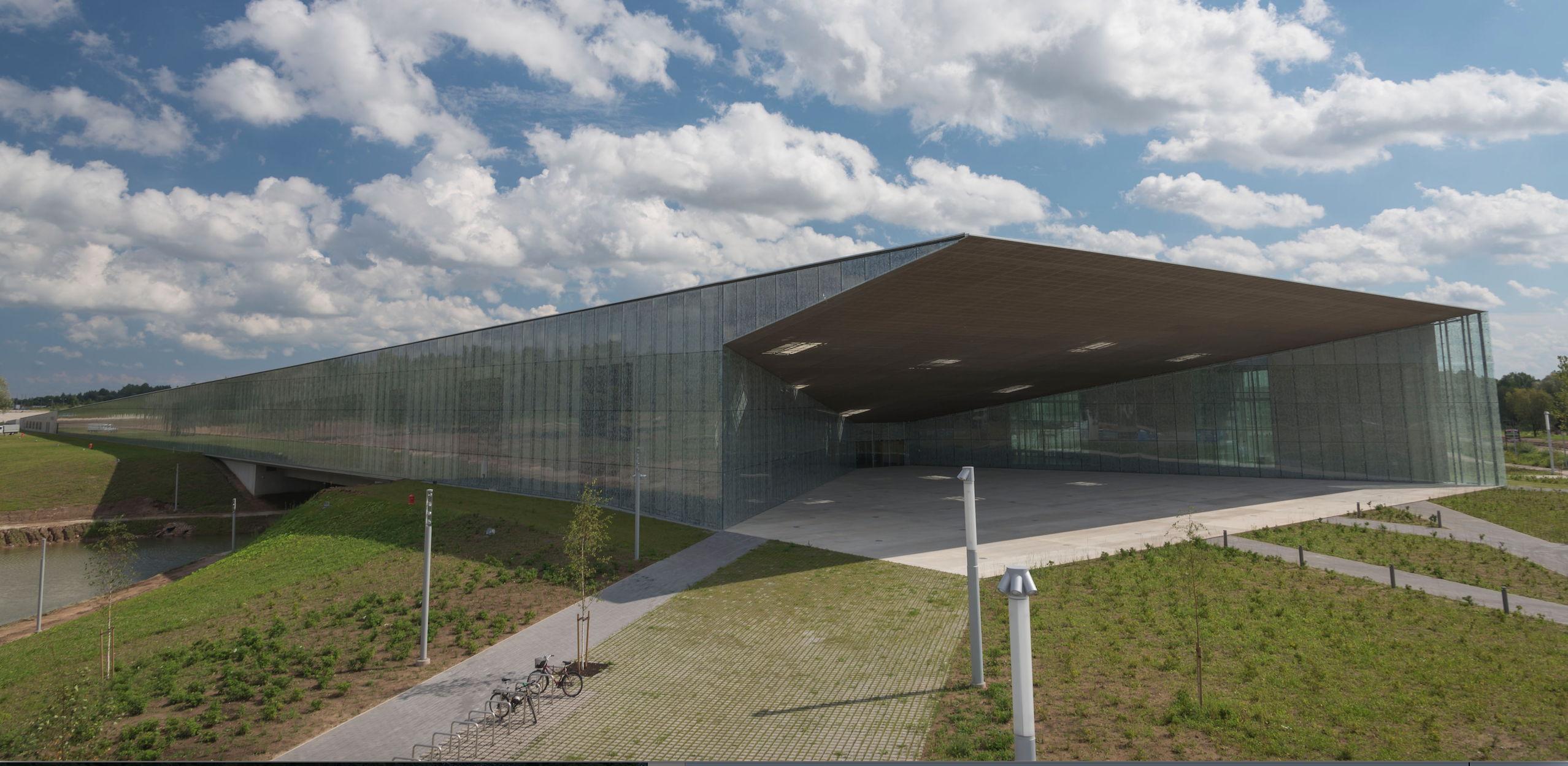

The current building, opened in October 2016, was built after the concept of a dynamic international team of young architects (Dorell.Ghotmeh.Tane.Architects). The project Memory Field positioned the new museum building at Raadi as an imaginary extension to the one-time aircraft runway, as the Raadi Estate had been transformed by the Soviets into a military base and airfield for nearly half a century. For the general public in Estonia, it had seemed previously unthinkable to incorporate the Soviet occupation into the discourse on Estonian identity in the context of representation, presented by the Estonian National Museum.

From an international standpoint, the ENM as a research institution has had a specific status due to its location between the East and the West. Experience, obtained during the long-term research of the culture of various ethnic groups located in Estonia and Russia, is of special value namely due to its consistency.

Õunapuu, Piret 2003a. Eesti Rahva Muuseumi majaehitamise lugu 1909–1918. – Mäetagused 20, 146–161.

Õunapuu, Piret 2003b. Tegelaskond, kes kujundas Eesti Rahva Muuseumi. – ERMi aastaraamat XLVII, 11–46.

Õunapuu, Piret 2009. Sissejuhatuseks. Mõte sai teoks. – Õunapuu, Piret (koost.). Eesti Rahva Muuseumi 100 aastat. Tartu, 10–101.

Kuutma, Kristin et al 2015. Estonian National Museum. Research report for the EUNAMUS project consortium.

Eesti Rahva Muuseumi 100 aastat. Koost. Piret Õunapuu; toim. Toivo Sikka, Ivi Tammaru. Tartu: Eesti Rahva Muuseum, 2009.

Juurtega sajandite mullas: kogumik Fr. R. Kreutzwaldi nim. Kirjandusmuuseumi 50. aastapäevaks. Toim. M. Kahu. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1990.